Latest in: Editorial

Sougwen Chung, Omnia Per Omnia Performance. Photo by Irina Abraham. "In Omnia Per Omnia Sougwen Chung explores collaborating with robots as opposed to using them as a tool. As I enter the room, the artist and …

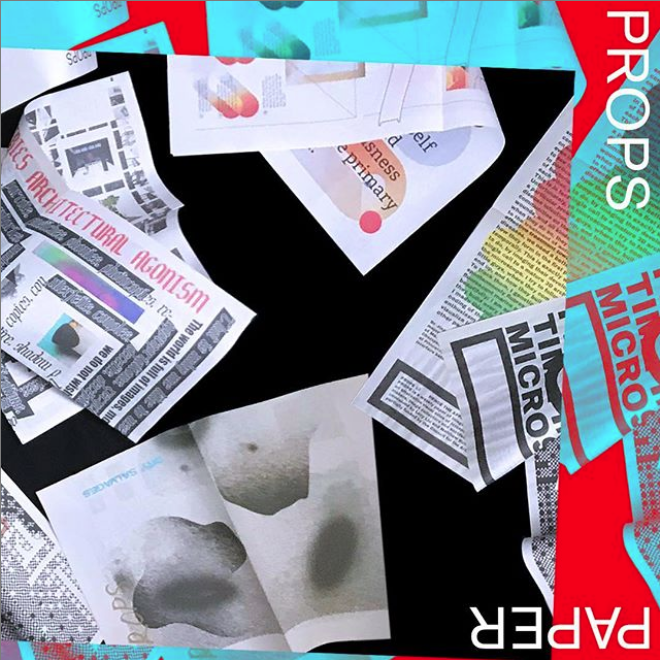

Vermilion Sands: Interview with Sougwen Chung VORTEX PROPS: What is the role of images in your research? Sougwen Chung: The role of images in my research is linked to ways in which interface design …

by Lindsay Howard | Oct 26, 2017link Humans have an innate need to adapt and improve what surrounds them. The strong desire to create a better, more meaningful future can be seen through each culture’s artistic …

Interview by Mimi Wonghttp://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/104 I love the point you bring up in your discussion about "image-making," specifically teaching machines how and what to see. In many ways, I feel that's often the role of …