Latest in: Press

Originally published in Ravelin MagazineInterview by Jillian Billard Hi Sougwen! Hi, Jillian ~ I always like to start with talking about an artist’s background. Can you talk a bit about your early life and …

Sougwen Chung, Omnia Per Omnia Performance. Photo by Irina Abraham. "In Omnia Per Omnia Sougwen Chung explores collaborating with robots as opposed to using them as a tool. As I enter the room, the artist and …

This post was originally published by NEW INC on April 20, 2018 and is based on an interview between Lindsay Howard and Sougwen Chung. Recently NEW INC, the New Museum’s cultural incubator, and Nokia Bell Labs presented their …

By Sougwen Chung In response to The Architect is DeadPublished by Architectural Association in London The proliferation of computation is bringing about a paradigm shift. From marks made by hand toward marks made by …

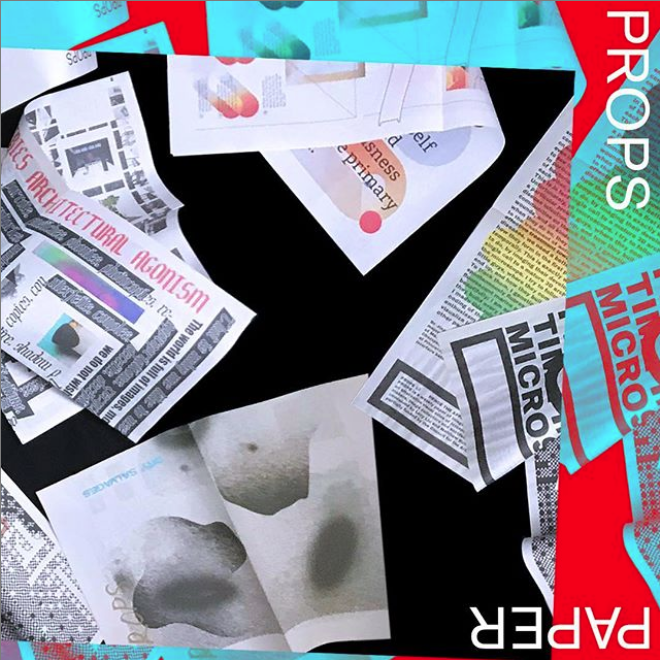

Vermilion Sands: Interview with Sougwen Chung VORTEX PROPS: What is the role of images in your research? Sougwen Chung: The role of images in my research is linked to ways in which interface design …

by Lindsay Howard | Oct 26, 2017link Humans have an innate need to adapt and improve what surrounds them. The strong desire to create a better, more meaningful future can be seen through each culture’s artistic …

Interview by Mimi Wonghttp://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/104 I love the point you bring up in your discussion about "image-making," specifically teaching machines how and what to see. In many ways, I feel that's often the role of …