Latest in: Press

‘In Search of the Present’ at Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Finland was selected as one of the 10 best art exhibitions to see in 2023, by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith. "What is …

From the AI for Good Website Increasingly, multidisciplinary artists and creative technologists are guiding the bleeding edge of innovation, and establishing crucial new narratives for wider society. In this episode, Sougwen Chung will offer …

The Victoria & Albert Museum has acquired my project MEMORY, created with Drawing Operations Unit: Generation 2 (D.O.U.G._2). MEMORY consists of an RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) model contained within a newly designed and developed …

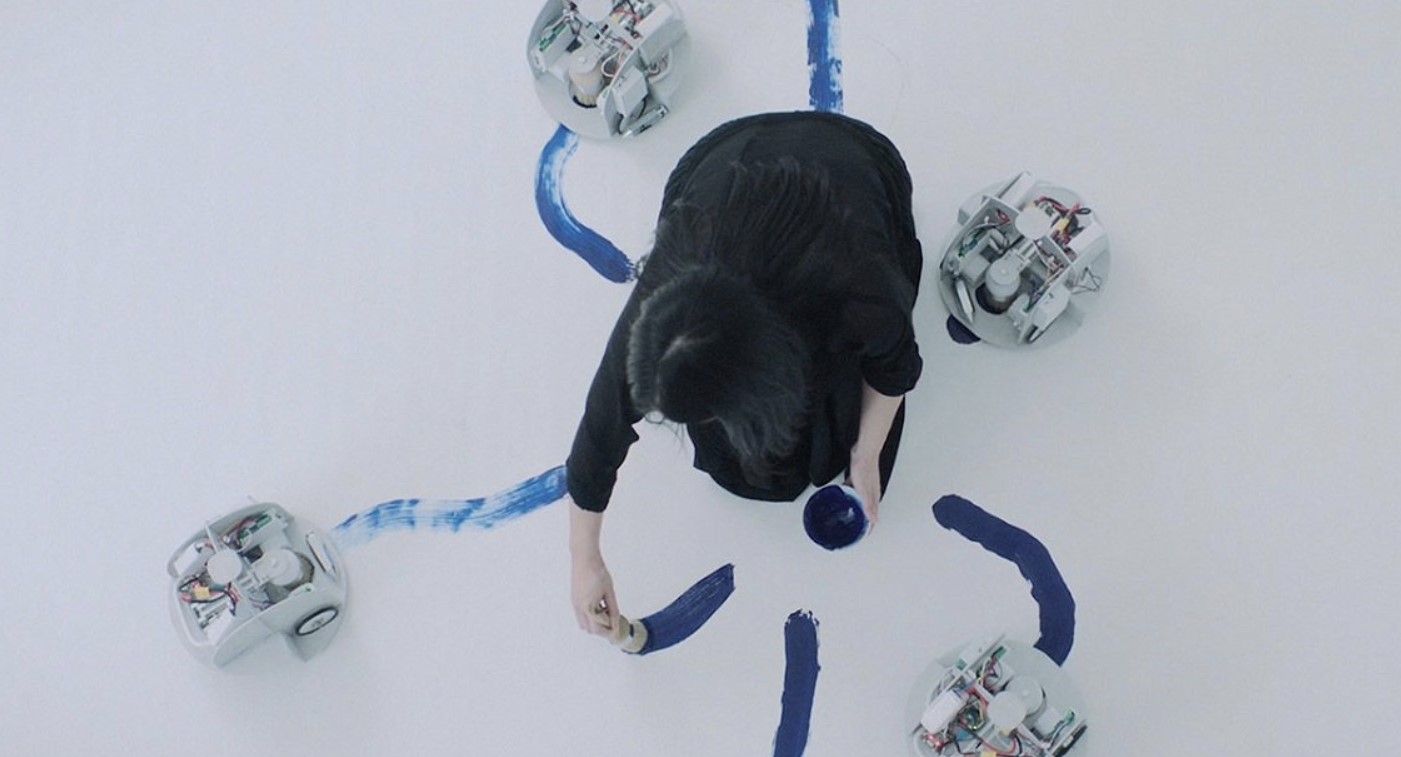

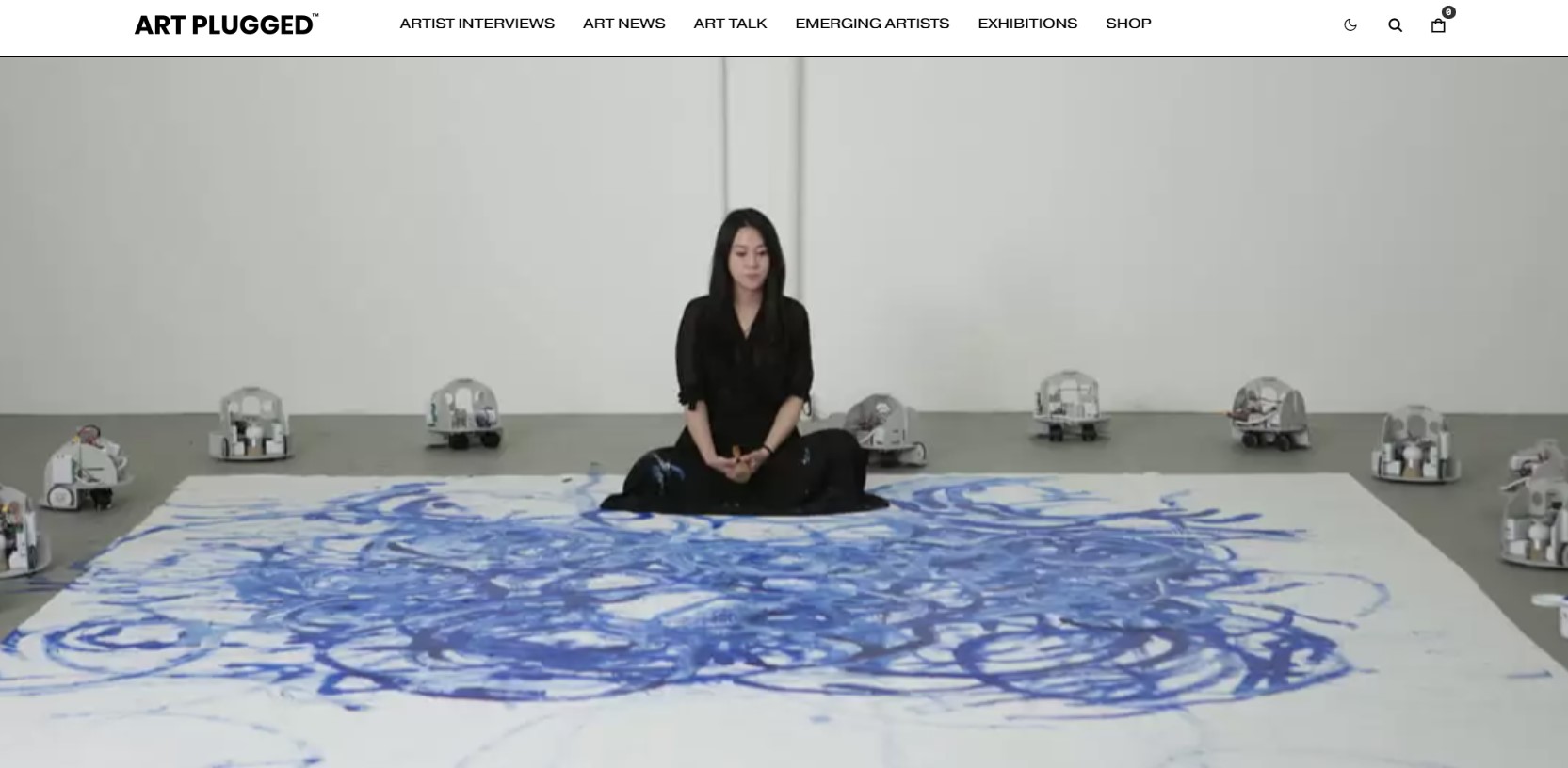

CLOT Magazine has written a feature on Assembly Lines (D.O.U.G._5), on show at EMMA Museum in Espoo, Finland. Read the article here: Insight: Assembly Lines by Sougwen Chung, states of meditation through multi-robotic kinematics …

Inner Magazines featured Assembly Lines, which premiered at the exhibition In Search of the Present at EMMA - Espoo Museum of Modern Art in Finland. Read the article here. October 24, 2022

The Imitation Game Whether it’s quaint or creepy, Artificial Intelligence is shaping the way we see the world. by Meredyth Cole April 4, 2022 5:00 PM DeepDream, BIG, *airegan. The list of artists and designers included …

‘Entangled Origins’ is a new, progressive exhibition from award winning artist Sougwen Chung, taking place during Frieze Week with Gillian Jason Gallery at Asia House, 12th-17th October. Sougwen Chung is an internationally renowned artist and …

“Science transforms its languages; Poetry invents its tongues.” Thank you to Falling Walls for the award of winner in the category of Science in the Arts for my contributions to the field of Art …

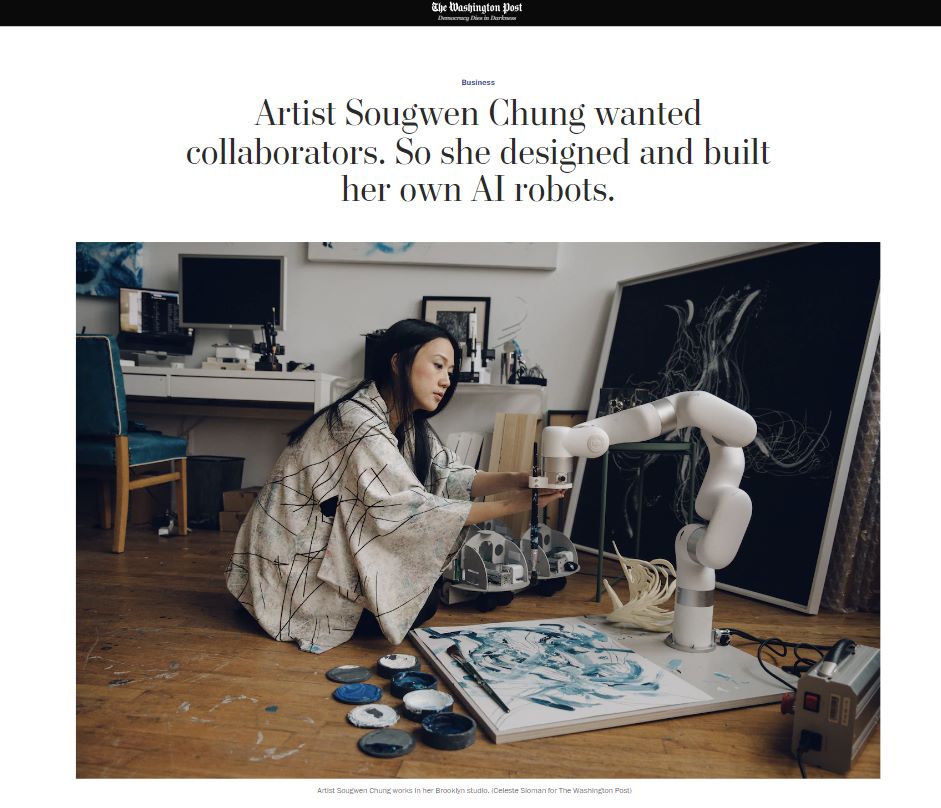

By Sarah L. KaufmanNOVEMBER 5, 2020NEW YORK — Sougwen Chung looks down at her silent, stubborn collaborator with a mix of affection and mild vexation. “I need to debug the unit,” says the 35-year-old …

Exploring ideas of authorship and agency in a future where technology is embedded in our culture, Chinese-Canadian artist Chung shares her thoughts and tells us about her practice. by Shraddha Nair Published on : Sep …