By Sarah L. Kaufman

NOVEMBER 5, 2020

NEW YORK — Sougwen Chung looks down at her silent, stubborn collaborator with a mix of affection and mild vexation.

“I need to debug the unit,” says the 35-year-old artist. “It won’t cooperate with me today.” She strokes the silver-and-white contraption as if she’s soothing a child. Clearly, it is more to her than a “unit.” It’s a robotic arm that paints, powered by artificial intelligence.

Meet Doug. Full name: Drawing Operations Unit, Generation Four. Chung uses it and other robots in her performance-based artworks. She and the robots paint together on large canvasses, part team effort, part improvised dance.

In pre-coronavirus days, Chung led these AI-assisted painting performances in front of a live audience, on a stage or in a gallery setting. At London’s Gillian Jason Gallery, a series of four of Chung’s robot collaborations is priced at 100,000 pounds, or more than $131,000, per image.

Yet with the pandemic, Chung is no longer performing live. She streams her robot collaborations from her studio into exhibit spaces — in August, the Sorlandets Kunstmuseum in Norway hosted several of these transmissions, where they became temporary video installations.

Chung has carved out her niche in the expanding world of AI art. Much of this world is focused on the digital side: graphics, pixels, software. But Chung’s work is different. She’s interested in a human-machine partnership, and what that feels like in the body.

“I’m interested in the physical world as well as digital,” she says, “not so much an emphasis on pixel manipulation. How these systems can feed back into our everyday lives, and in muscle memory and physical space.”

This is why she likes people to see how she and the robots paint together. She calls her work “embodied AI,” and it’s her body she’s talking about — bending or kneeling, wielding her brush on the canvas with her robots, responding to their movements as they respond to hers.

I was interested in the physical embodiment, and what it would feel like to evolve my own drawing practice, and I hadn’t seen robots used collaboratively at that time.

Sougwen Chung

Chung has designed and programmed about two dozen Dougs, at a cost of up to $8,000 per unit. She uploaded the early ones with 20 years worth of her drawings, making them experts in her gestures. Doug 4 is even more intimately tied to Chung: It connects to her brain-wave data, and this influences how the robot behaves. When she and her robots paint, they are closely linked through a shared bank of knowledge, and through live, in-the-moment visual and movement cues, just as dancers or musicians are.

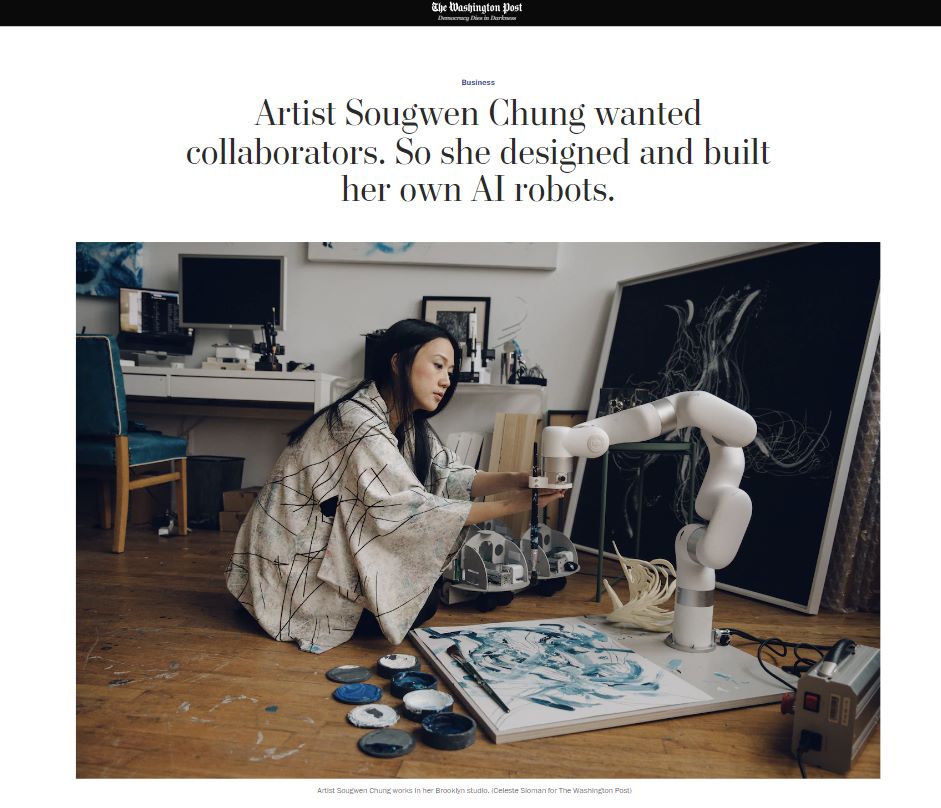

In Chung’s Brooklyn studio, Doug’s arm bends over a sheet of paper on a table, with its front tip poised just above the surface, ready to be fitted with a brush. Smooth and organic-looking, this Doug could be taken for a biomorphic sculpture. You could say it’s both art object and art maker.

Paintings that Chung has created with AI systems hang on the sun-washed walls of her studio: spiraling clouds of blue and white; tendrils that spring forth and recede; fluid lines worming together in an undulating web. Some recall thick-inked calligraphy, the jottings of a secret language.

They look like the work of a single artist. But are they? That depends on how you think about AI. It’s a term that even Chung hesitates to embrace.

When Sougwen Chung and her robots paint, they are closely linked through a shared bank of knowledge, and through live, in-the-moment visual and movement cues. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

When Sougwen Chung and her robots paint, they are closely linked through a shared bank of knowledge, and through live, in-the-moment visual and movement cues. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

Sougwen Chung has designed and programmed about two dozen Dougs, at a cost of up to $8,000 per unit. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

Sougwen Chung has designed and programmed about two dozen Dougs, at a cost of up to $8,000 per unit. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

“We don’t have human intelligence figured out,” she says. “That lack of specificity is not the best way to think about a complex set of systems.”

She prefers to call her robots collaborators. They don’t fully replicate the human creative process, of course, but neither are they simply spitting out copies of the data Chung feeds them.

Instead, they can generate interpretations — for example, expanding upon a data set of Chung’s drawings to make their own designs. They can also respond spontaneously to Chung’s lines and brushstrokes, creating a feedback loop with her of improvised, communal creation.

Chung made the paintings on her walls with mobile Dougs, Generations Two and Three, that scoot around on wheels with their brushes, trailing paint. (First, she had to figure out how to keep their wheels from slipping on it.) Many of these floor-based units rest on shelves and tables around the studio. They’re round and Roomba-size, topped with coiled wires, small motors and a compact computer device known as a Raspberry Pi. Built into the front of each one is a short, stiff chalk brush, like a shaving brush.

Dressed all in black — snug T-shirt, Harem pants — Chung looks more like a dancer than a techie, with her slender physique and expressive, delicate hands. She worries about sounding “too much like a nerd” as she points out the robots’ features.

Although she speaks softly and has a calm demeanor, Chung is a bit of an adrenaline junkie. She’s okay with chaos, happy to throw control to the winds. Why else would she choose this path, turning away from safe, contemplative work in her studio to build a career out of risky group projects in public view, with unpredictable algorithms and glitch-prone, high-maintenance machines (looking at you, robotic-arm Doug) that require constant calibrations?

For Chung, perseverance while dealing with technical glitches is nothing new. She grew up at the intersection of art and technology; her father was an opera singer and her mother a computer programmer. Born in Hong Kong, they emigrated to Toronto, where Chung was born. She studied violin, taught herself to code and began designing websites in grade school.

She was also fond of drawing, though back then she didn’t envision a career as an artist. Still, she liked her work enough to hang on to her early sketches, and to everything since. (This is a highly organized person.)

“The drawing practice,” she says, “is something I’ve always kept with me, my whole life.”

It was during a research fellowship at MIT Media Lab that Chung discovered robotics. Here was a way to bridge science and art, and build on her sketching.

[These artists make online disinformation into art. Or is it the other way around?]

“I was interested in the physical embodiment, and what it would feel like to evolve my own drawing practice,” she says, “and I hadn’t seen robots used collaboratively at that time. I wanted to try something less about robots executing an existing code and more about working together.”

In 2014, she launched the machine collaborations that eventually included AI. “It was just this strange experiment,” Chung says, thinking back on the first AI system she built and coded. “What would it be like to have a drawing collaborator that was a nonhuman machine entity? What would that do for my process?”

It sounds like a logical progression — from child artist and coder to professional artist building her own robots. Yet Chung says none of this seemed very clear as she was feeling her way into this new realm.

Sougwen Chung says she prefers to call her robots collaborators. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

Sougwen Chung says she prefers to call her robots collaborators. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

“I stumbled into my path,” she says. What pushed her forward wasn’t so much the technology, fascinating as it was, but the rush of performance. That’s what she had loved about playing violin as a child.

“I wanted to bring the body back into the creative process, the muscle memory and gesture that were missing from my practice, and that energy you create with the audience.”

Maya Indira Ganesh, a technology researcher at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany, says Chung’s work stands out because she rejects prevailing notions of robots and AI, and she’s comfortable with her own fallibility.

“What Sougwen does is say, ‘How do we reimagine these boundaries and differences that are supposed to exist between humans and machines?’” Ganesh says, speaking by phone from Berlin. In galleries, “most of the AI art you see is usually simple and straightforward, like watching computation happen. It’s the fetishization of the machine. We think these systems should be perfect and seamless. But Sougwen is very skilled with this technology, and she talks about her works in progress and in process. … She’s showing us that the human is very much a part of the process.”

The modern human is surrounded by smart technology and phones and machines, and I want to use them as a source of inspiration, looking to what future art practices could be.

Sougwen Chung

The process. Think experimental theater. Typically, Chung and Doug perform in a darkened gallery space, with spectators (pre-pandemic) gathered around a canvas illuminated on the floor. There’s often music and atmospheric lighting, and the robot is sort of crawling around.

“Painting, painting,” says Chung, delivering a firm correction with a smile.

Of course. It’s painting. (One of the Dougs, perched beside Chung’s laptop as we watch videos of her performances, still has dried blue and white paint stuck to its little brush.) Doug dashes off gleaming streaks of color, and Chung counters with her own, and so on, artist and machine taking turns reading each other’s painted expressions and building on them. The robot is guided by an AI system known as recurrent neural networks.

“It’s more of a call-and-response,” Chung says. “I can input different line strokes and the machine can respond to it. So it’s really about that interaction. But it’s also not about making machines do a thing. You know what I mean? It’s always about that feedback loop in that collaboration.”

Sougwen Chung paints in her Brooklyn studio. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

Sougwen Chung paints in her Brooklyn studio. (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

Interaction. Collaboration. Chung’s language reveals how she thinks about AI. It’s not her slave. She’s not always the boss.

“I think a lot about narratives that we tell ourselves about technology and why we have those narratives,” she says. “And I think they’re really influenced by science fiction and pop culture. And that tends to be hypermasculine, hyper-dystopian. That’s why we have all these really sensational stories about AI, like, is it going to take over humanity? Where do we get that from? We get that from ‘The Matrix.’

“That’s not a narrative that I subscribe to,” she continues. “I think it creates a very adversarial, power-driven dynamic with technology.”

In the performances, everything comes together: Her tech expertise, her art, the full-body experience. After all the programming and calibrating, it is through these improvised painting experiences with her AI collaborators that Chung has regained the flow state she loved as a musician.

“Where you don’t have to think about commas in your code,” she says, “but you can just be in it. … There was this sense of exploration and wonder that I was navigating. It felt very vital and alive, like dance.”

Her work continues to evolve. In a recent project, she uploaded her robots with publicly available surveillance footage of pedestrians crossing New York City streets. She extracted specific data streams, to capture the physical motion of pre-coronavirus New York crowds. With the robots, she turned this digitized bustle into brushwork. In future projects, Chung hopes to bring the public into her process and even onto her canvas, to draw alongside the robots.

“I’m curious about exploring what the machine would draw like,” she says, “if we all contributed to a drawing set.”

Ultimately, Chung wants to use AI technologies to bring people together. Yet now that the coronavirus has us all practicing social distancing, she sees other opportunities: ways for viewers to experience AI art-making remotely, such as the streamed performances.

“Picasso used the tools of his day,” she says. “I’m interested in using the technologies that define our current moment, as a way of understanding how they work in our lives. The modern human is surrounded by smart technology and phones and machines, and I want to use them as a source of inspiration, looking to what future art practices could be.”

“There’s always a potential for failure,” Chung says. “With this dynamic that I’ve been exploring, it’s about the unexpected. And that keeps me really interested.”

“Picasso used the tools of his day,” Sougwen Chung says. “I’m interested in using the technologies that define our current moment, as a way of understanding how they work in our lives." (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)

“Picasso used the tools of his day,” Sougwen Chung says. “I’m interested in using the technologies that define our current moment, as a way of understanding how they work in our lives." (Celeste Sloman for The Washington Post)